How to Understand Chords and Keys

the Easy Way?

How to understand chords and keys if you don’t have any music theory background? Is it possible to get around it? Understanding why certain chords go together, why sometimes a chord is a major and sometimes a minor and dealing with multiple scales and terms can be really frustrating.

Even if you have some music theory knowledge, you have to study it pretty far to be able to understand and explain certain things. Most people simply don’t have the time to start solving this puzzle, let alone going deep with it.

The Problem with Music Theory

When I started to write my own music, I knew how to play power chords with a guitar, but didn’t really know what the chords were and called them by the fret my fingers were in (two, five, zero or whatever). I was playing mostly rock and metal. All I wanted was to make music of my own, but oh boy it was slow, since I didn’t really know what chords to use. I had to test everything by ear, which I was terrible at.

I had learned some music theory in school, but I felt like it didn’t really apply to the music I was playing. It didn’t explain it. Maybe that’s why I didn’t really care about the theory and got so confused by it.

When music theory is mentioned, it tends to drive people away. Even if you can and want to understand the theory, it gets way too complicated way too fast, and it doesn’t really explain what you’re looking for. There are always exceptions and aspects that don’t quite apply to your situation. “This is the theory, but you can also do it this way, for no particular reason.” At least it feels like it, because you haven’t gotten far enough with the theory.

Is there an Alternative Way?

Could chords and keys be explained simply, without the need of actual complexity of music theory? Is it possible to present all that stuff with plain and simple approach? See, everything can be really complicated, or really simple. I prefer simple.

I’m using simple drop tuning power chords as a way of explaining, because that’s the approach I used to have. That’s all I had, just the knowhow to play simple power chords and riffs from various frets. I know that’s the approach many aspiring metal and rock guitarists have. That’s the main reason why in this article I use a drop tuning. If you consider yourself as one of these people, bear with me, I promise to make this easy and understandable for you.

In Case You’re Using Standard Tuning Instead of Drop Tuning

In this post I’m explaining everything in drop tuning. In case you’re using standard tuning (E, A, D, G, B, E) instead of drop tuning (D, A, D, G, B, E), it’s fine, this will also apply to you. In drop tuning the lowest string is a whole step lower than in standard tuning. If a fifth fret is played in drop tuning, it’s a third fret in standard tuning. As well if a second fret is played in drop tuning, it’s a zero (open string) in standard tuning. As you already noticed, just go downward two frets and you’re fine.

How do Basic Chords Work and Which Chords Should I Learn First?

I’m explaining everything through simple power chords, but in order for you to thoroughly understand what I’m talking about, a simple chord forming must be instructed first. If you already know how to form a chord, then you can skip the next three chapters and go straight to the “Relative Minor and Major” section.

How to Form a Chord?

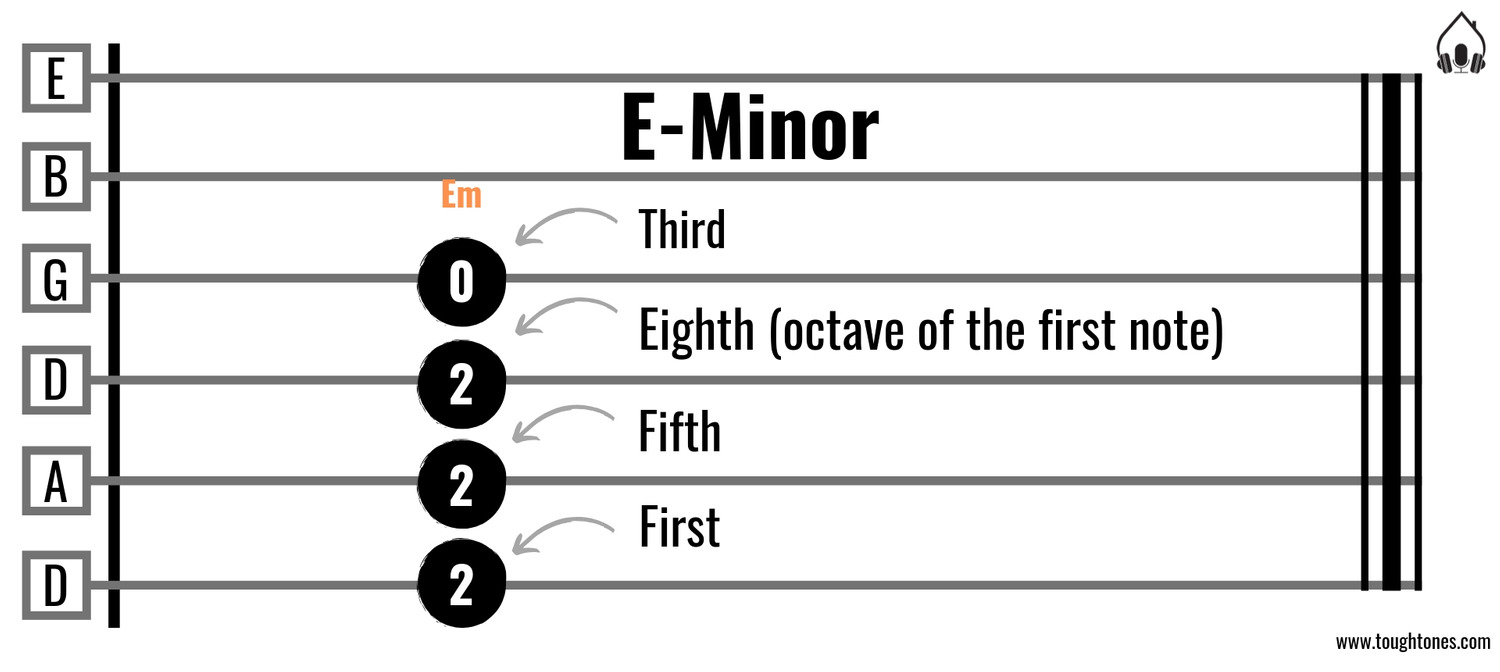

A simple chord contains three notes: first, third and fifth. The first one is the so called root note, that determines the name of the chord, for example if the root note is e, then we know that the chord is either E-minor or E-major. The third note is what determines if the chord is minor or major. Together with the fifth note these three notes create a chord. Usually an octave is added also. It’s the same note as the first, but an octave higher. Look at the picture below:

How to Know If a Chord Is a Major or a Minor?

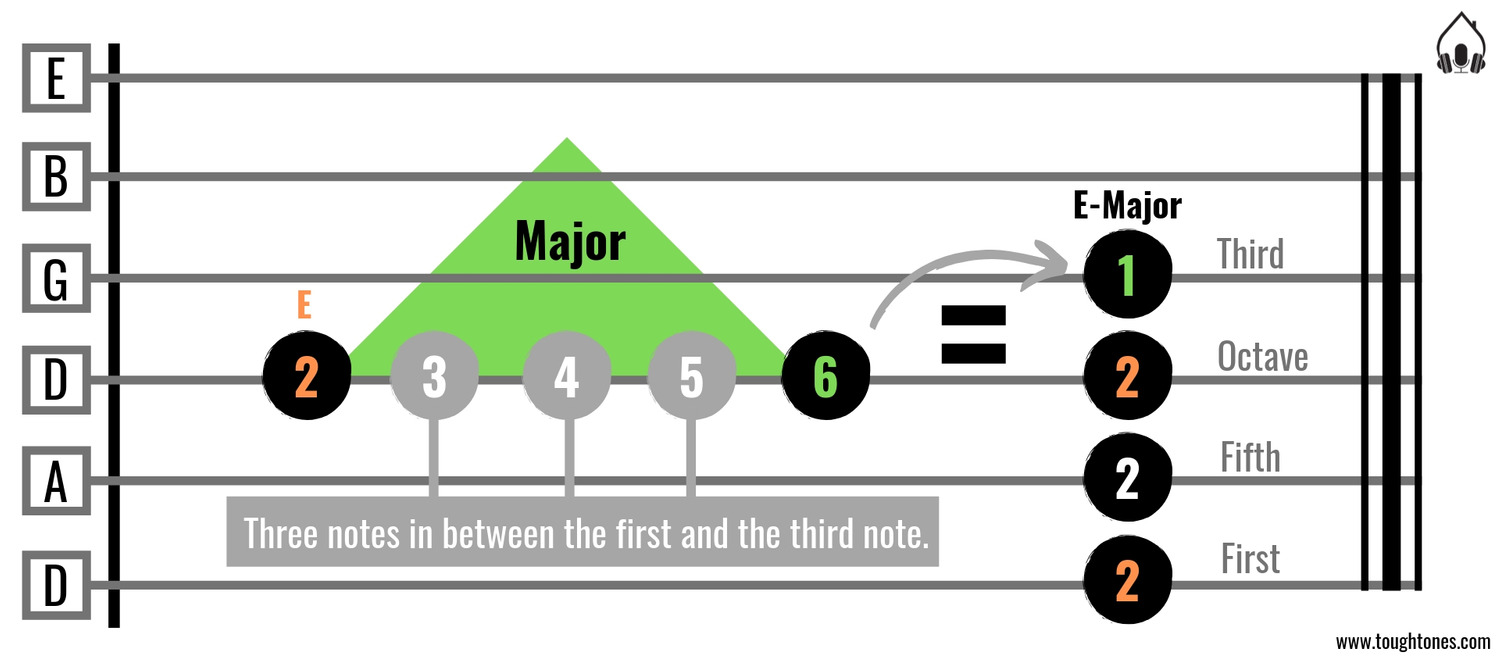

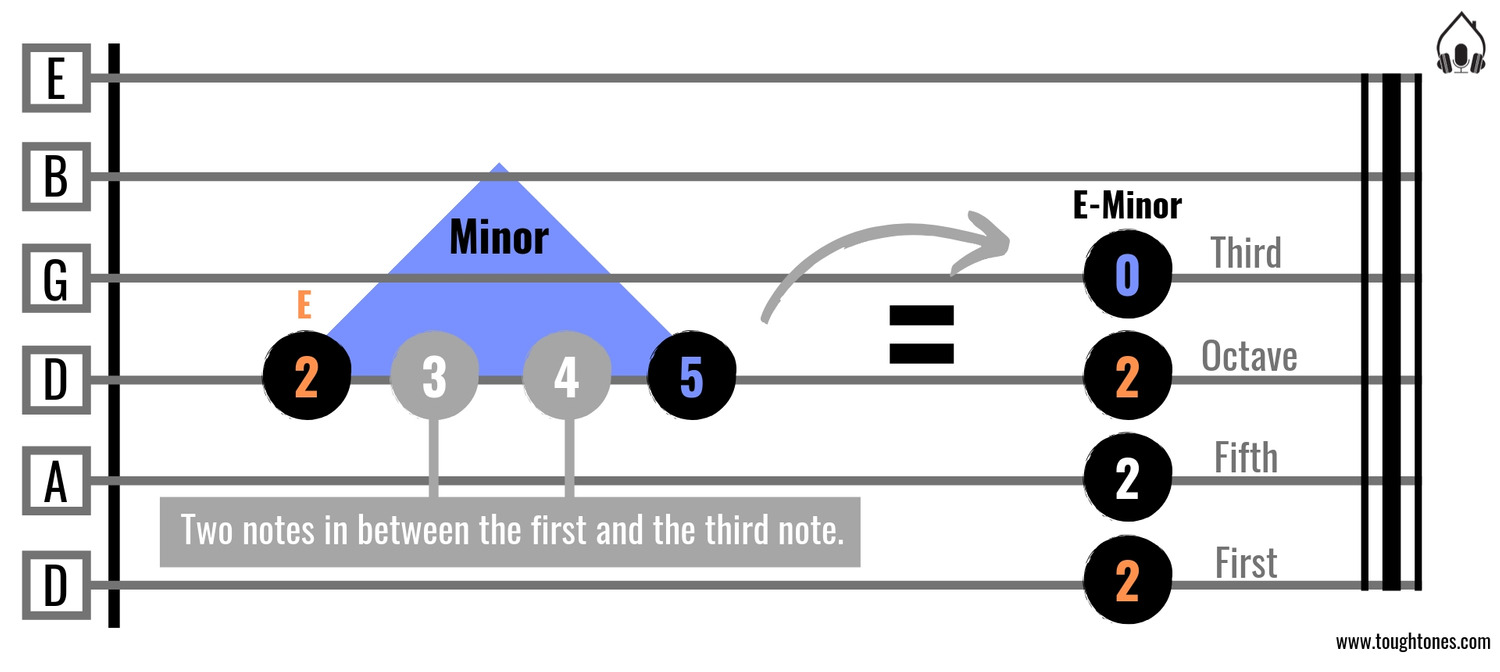

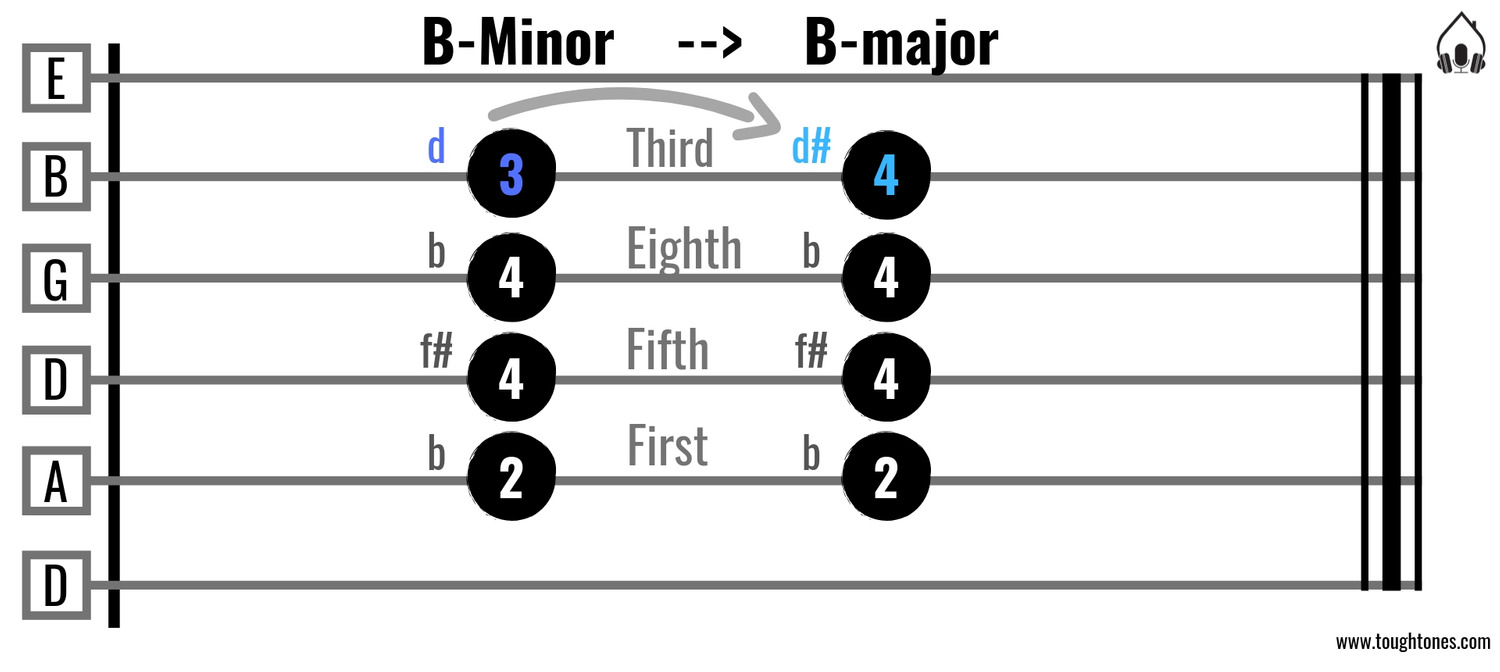

There are major chords and minor chords – as a rule of thumb, major sounds happy, whereas minor sounds sad. The distance between the first and the third chord determines if a chord is minor or major. There’s either three or two frets (notes) in between the first and third note. If the distance is two frets, the chord is a minor and if the distance is three frets, the chord is a major. Look at the pictures below.

It’s good to understand how minor and major chords are formed. However, if you’re using power chords like in this post, you don’t need to worry about them too much. That’s the beauty of them, they’re pretty simple to use. A few words about power chords before diving into the business:

Power Chord

A power chord (also known as a fifth chord) is a two note chord consisting of the first and the fifth note. The third note has been left out. As the third note determines whether the chord is minor or major, the power chord has no such quality in it. This means that you can play power chords without worrying about minors or majors. However, you can add an octave, as it makes a power chord a little bit bigger sounding.

So let’s not worry about the third note. You’re going to see power chords with the added octave from here on out. Even though there’s no third note in a power chord, I’m going to call them either minors or majors, depending on which they would be with the third note.

Relative Major and Minor

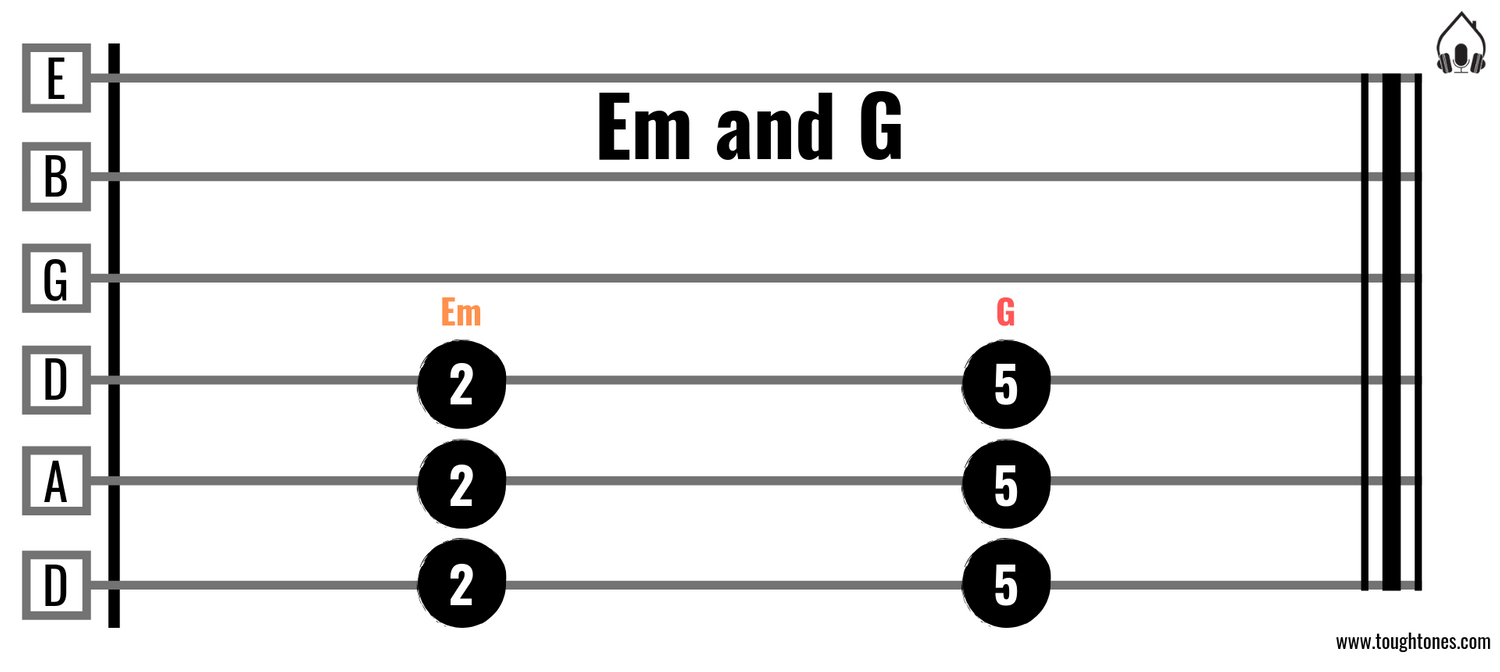

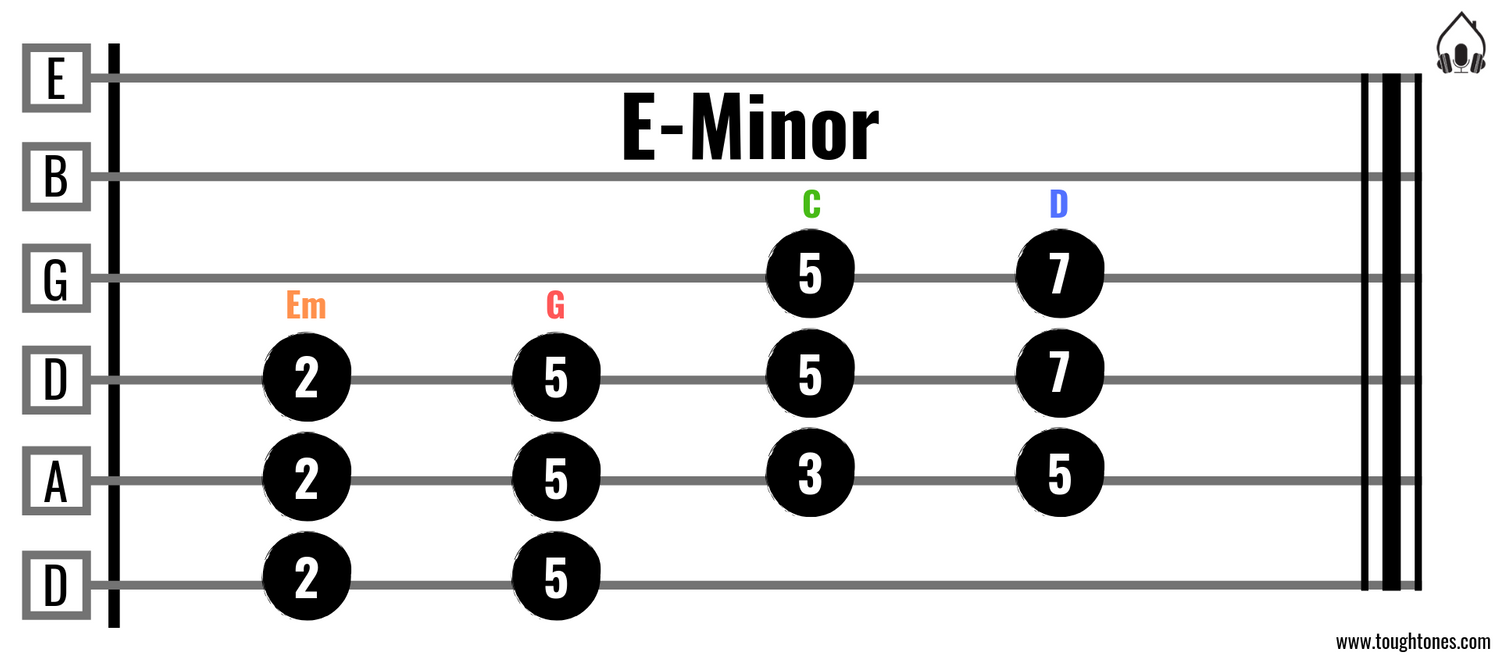

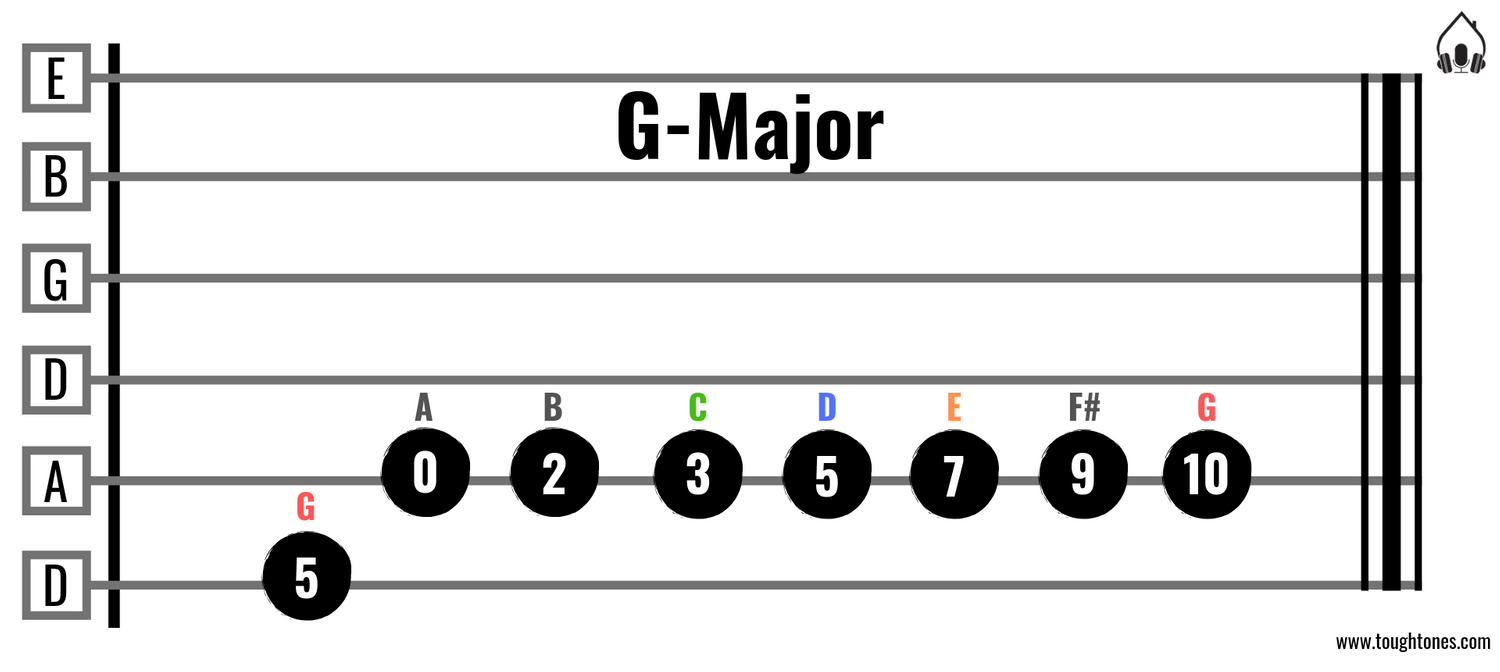

Now we’re getting into the interesting stuff, that will help you with your songwriting. All the major chords have a minor chord as their relative. Let’s take an example: G-major and E-minor, they’re relatives. Look at the picture below.

Why is this important? Because you can use the same chords around them, regardless if you’re playing a happy song (G) or a sad song (Em). They also fit together, so you can use them in the same song. They’re in the same key. What is a key? A key in music, is a bunch of notes (and chords) that go together in the same song.

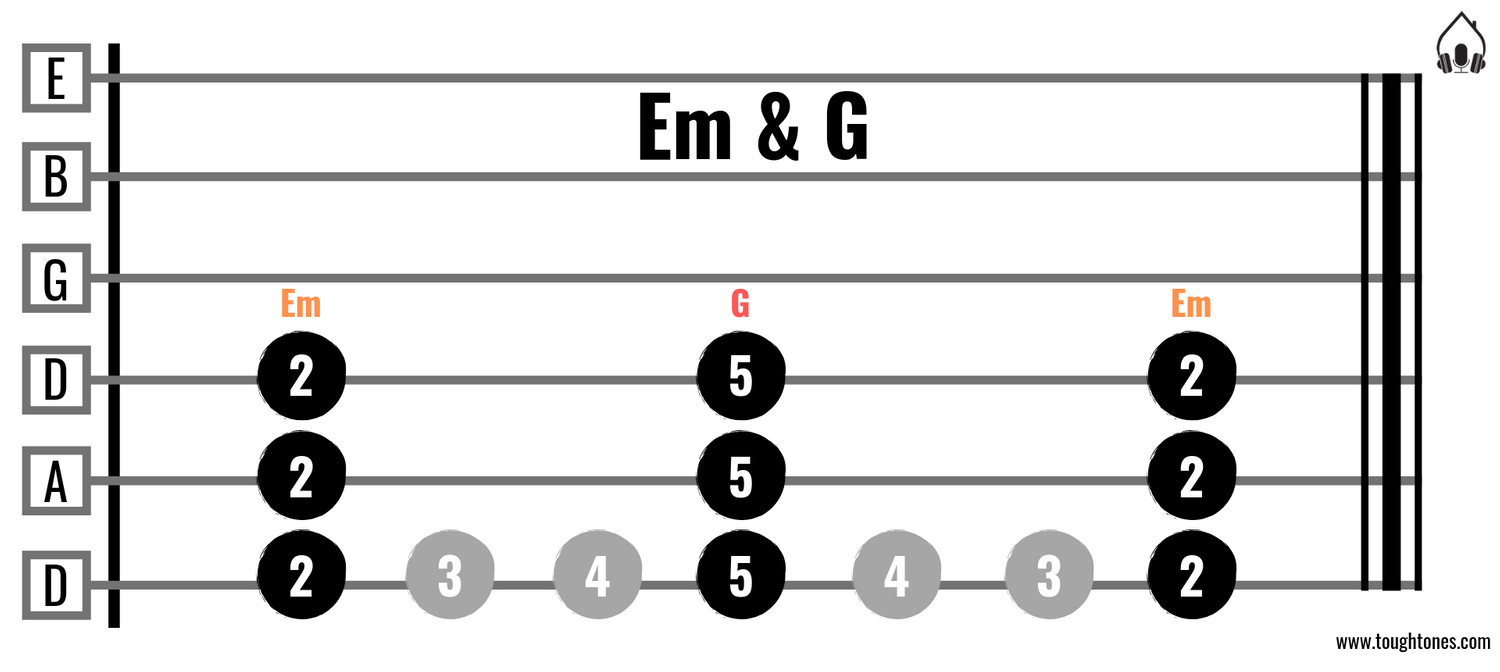

E-minor is the relative minor for G-major. You can find the relative minor, by going down three frets from a major. The same way you can find a relative major by going up three frets from minor. For example Em → G like shown below. There’s two frets in between them: G is on the 5th fret, Em on the 2nd, so in between them there’s 4 and 3.

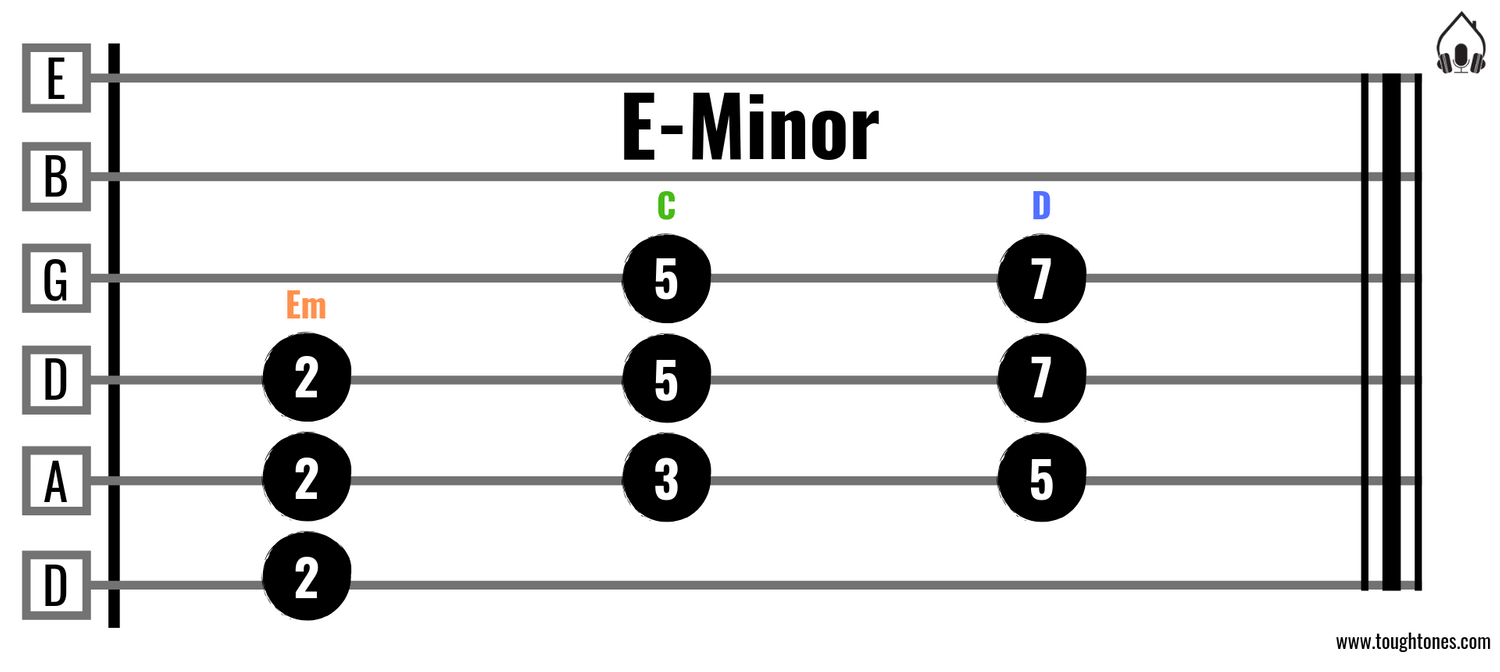

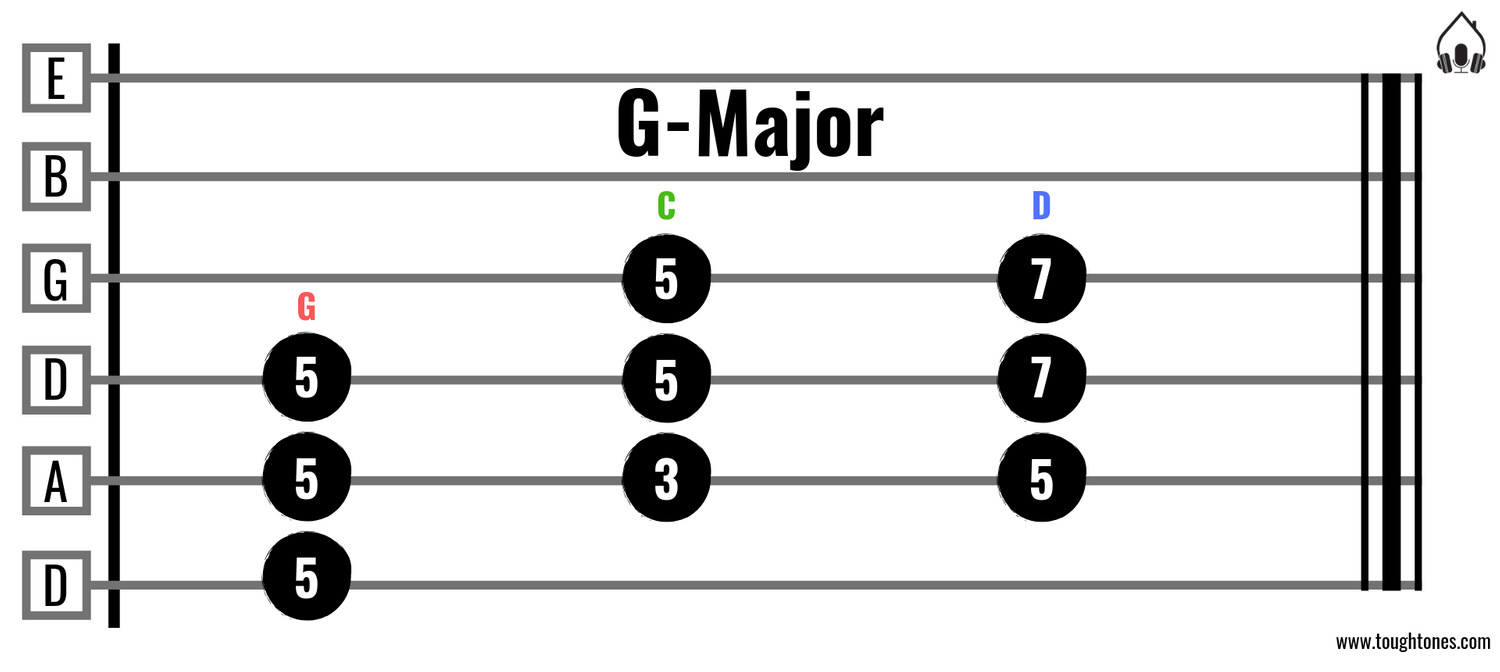

Great, so what chords go together with Em and G and why? The most commonly used chords with Em (and G) are C and D. If you’re playing a song from E-minor, C and D will fit. Likewise, if you’re playing a song from G-major, the same C and D will fit there also. Why they’re the most commonly used chords? Because compared to the first chord of a key, they create a certain movement that pleases the ear.

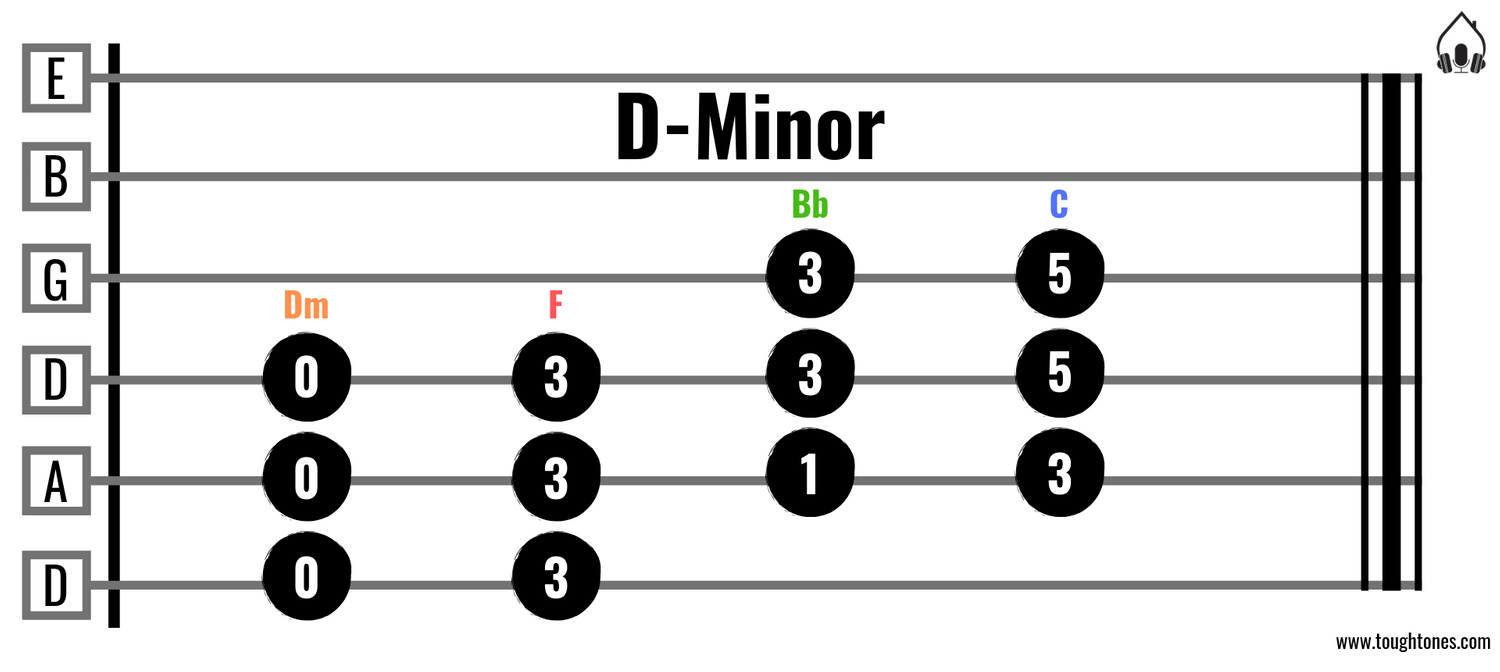

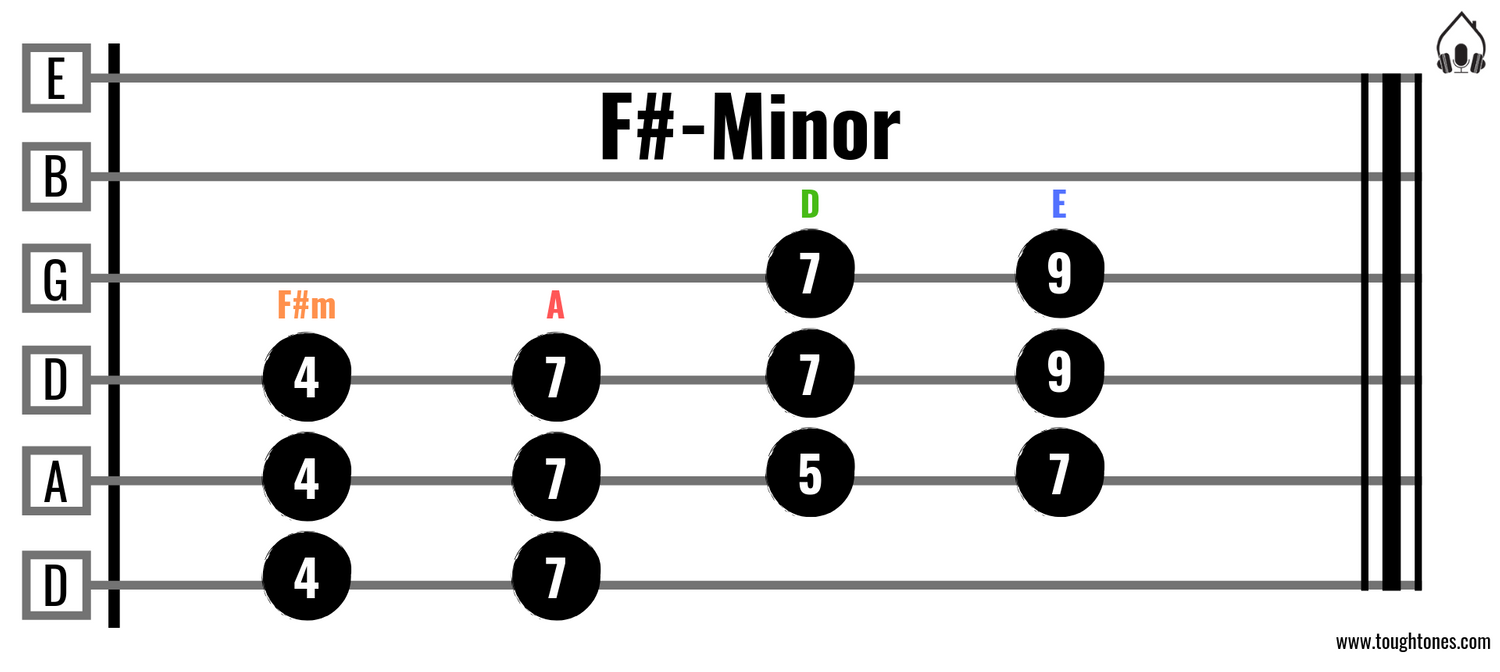

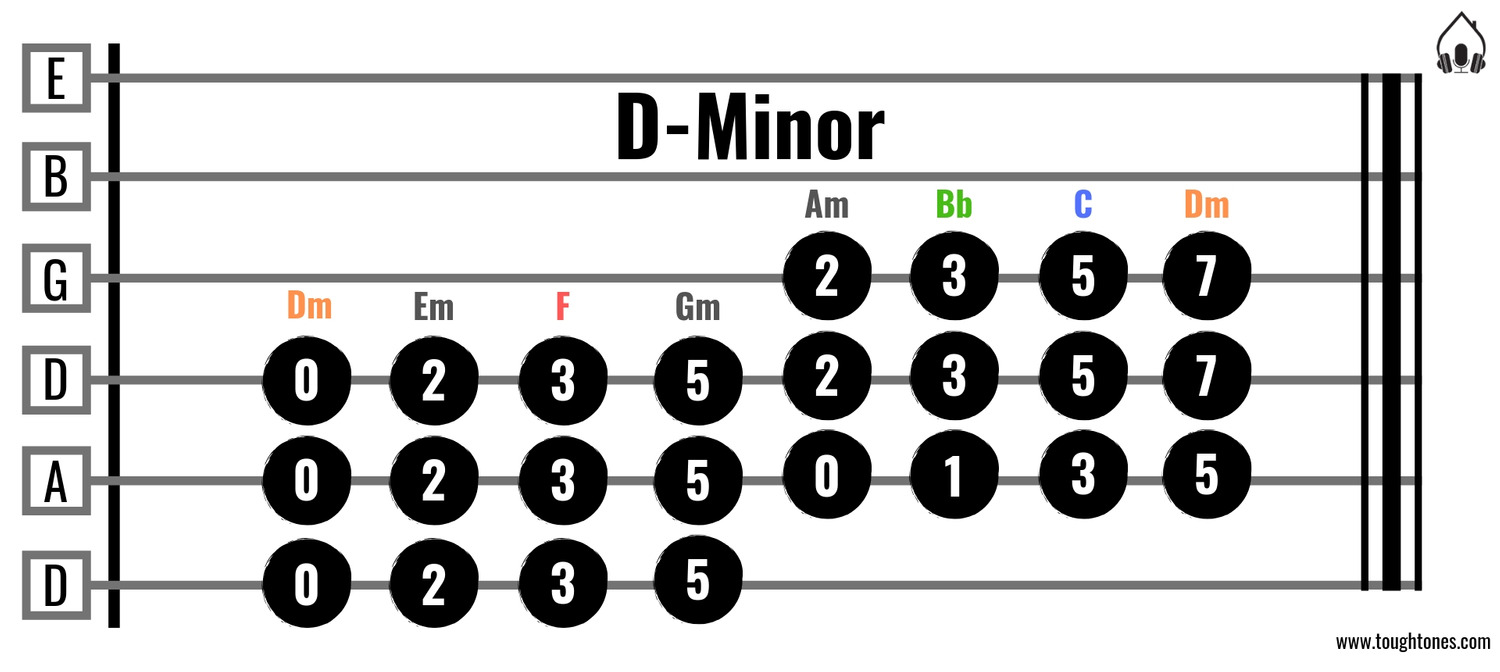

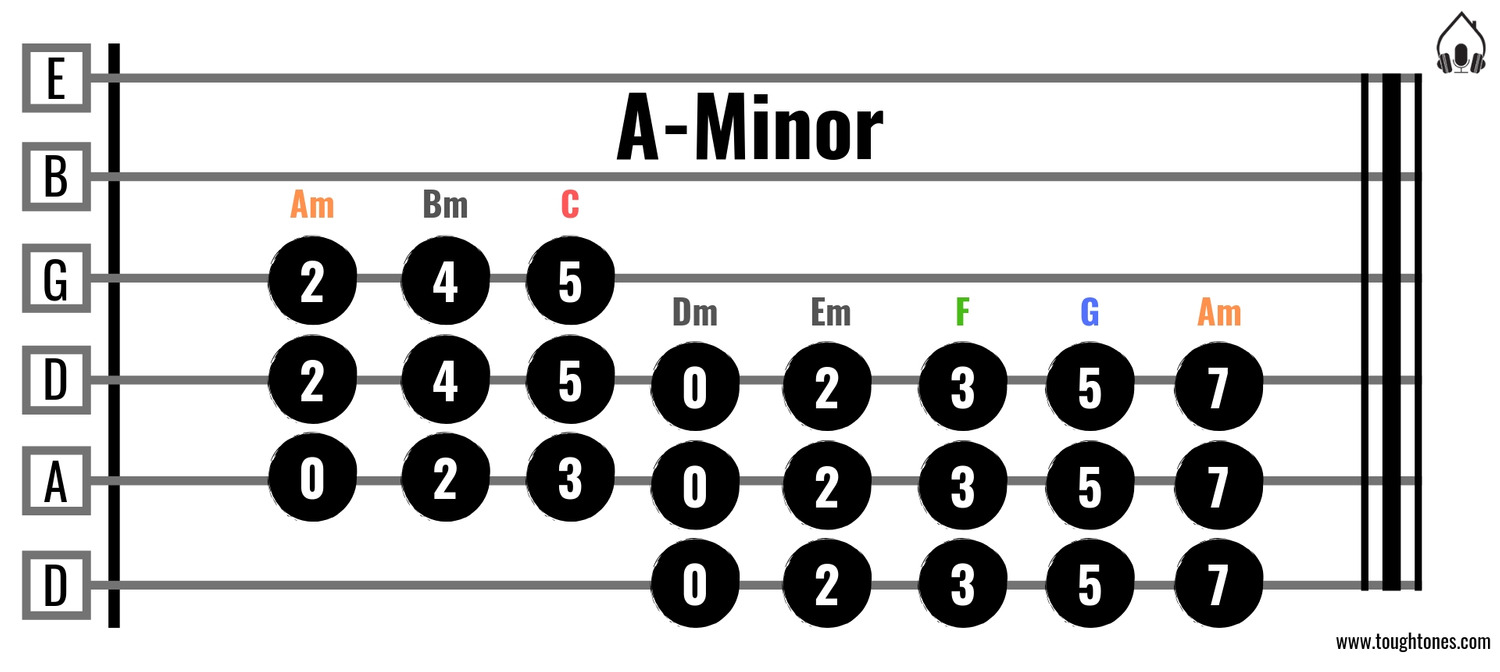

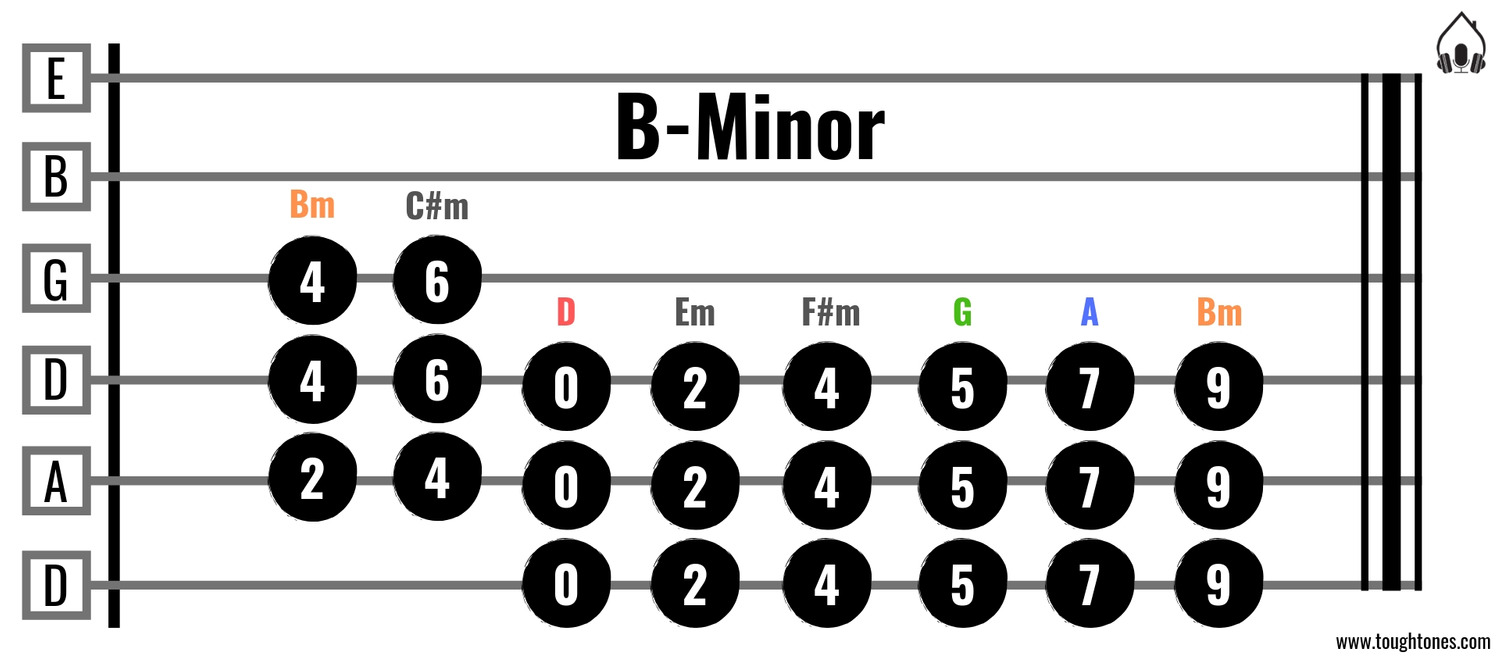

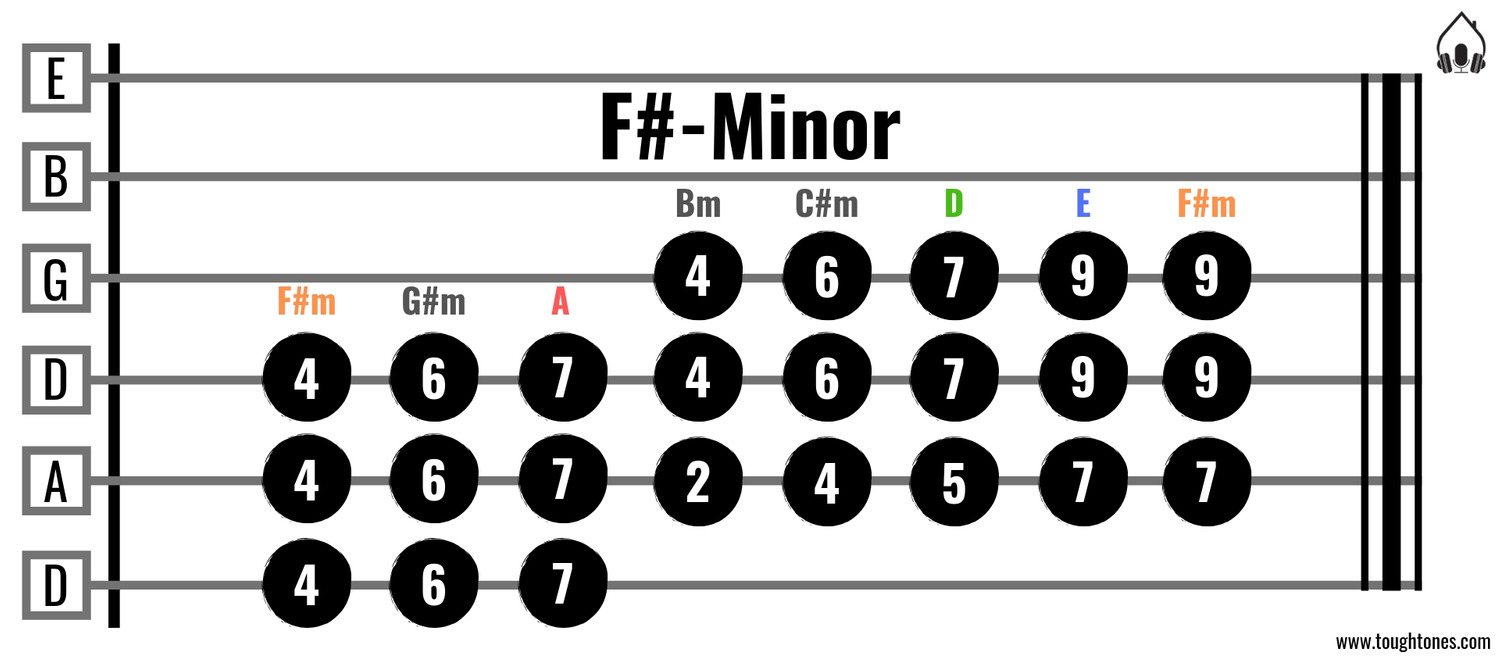

The beautiful part is, that you can use this same pattern in all of the different keys. You know that this same form of chords will apply, no matter which key you’re in. It’s the same movement whether you’re playing a song from D-minor, F#-minor, A-major or whatever. The distance between the chords remains the same, as seen below.

What Is a Key in Music? How Do You Know Which Chords Are in the Same Key?

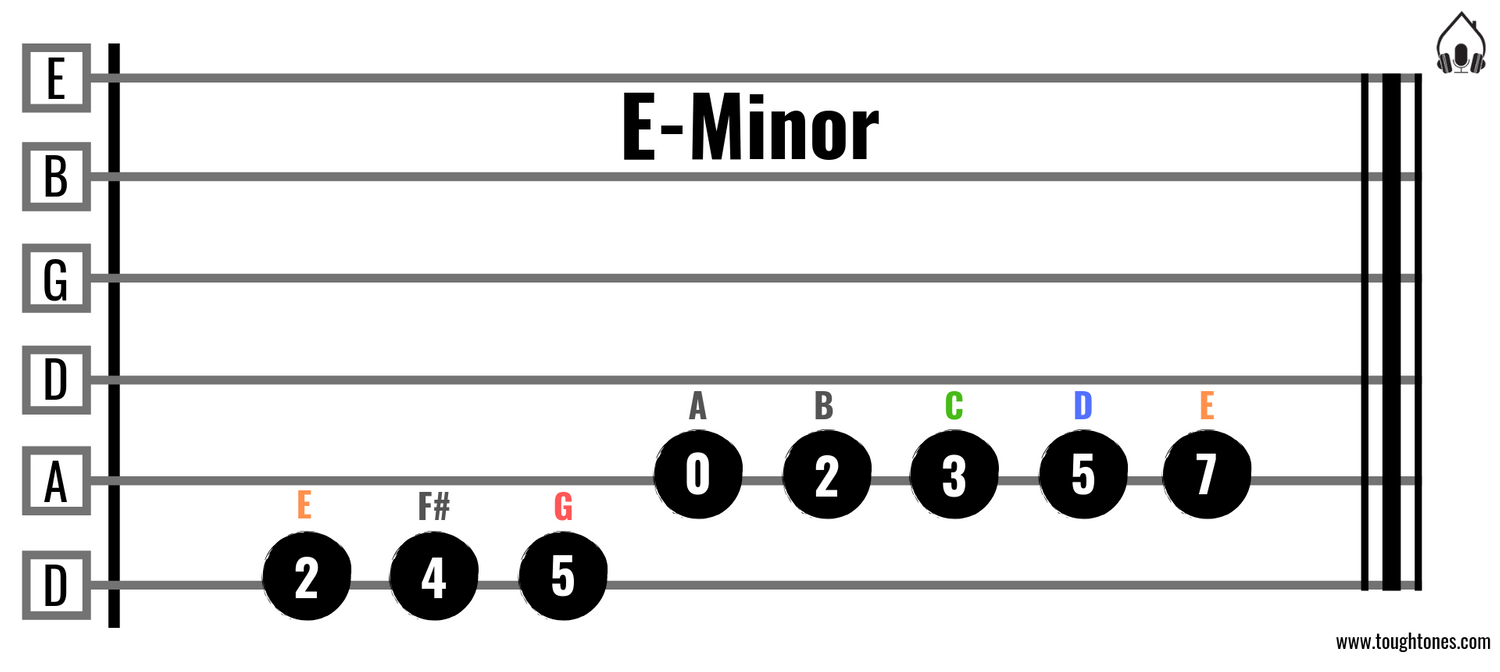

To put it simply, a key in music, is a group of notes that fit together in the same song. For example in E-minor, you have notes that you can use within that key, pattern of seven notes that repeat: e, f#, g, a, b, c, d.

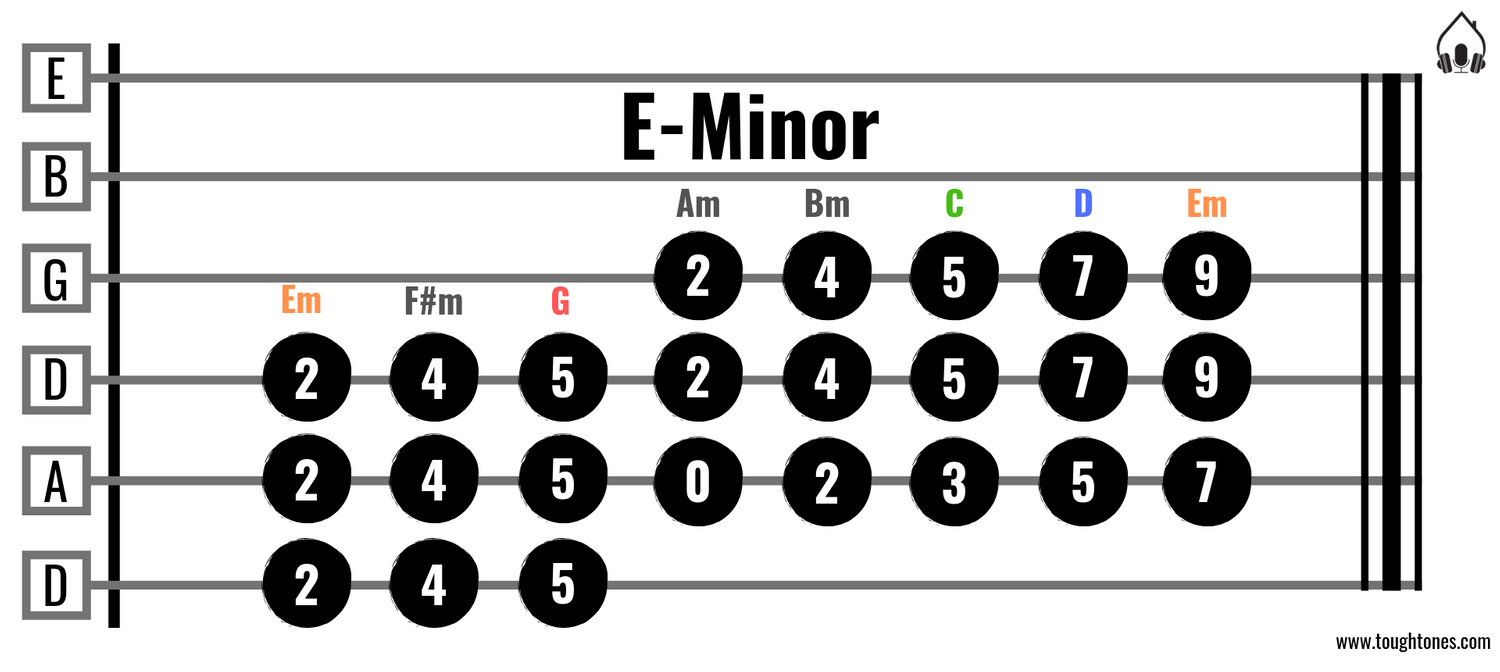

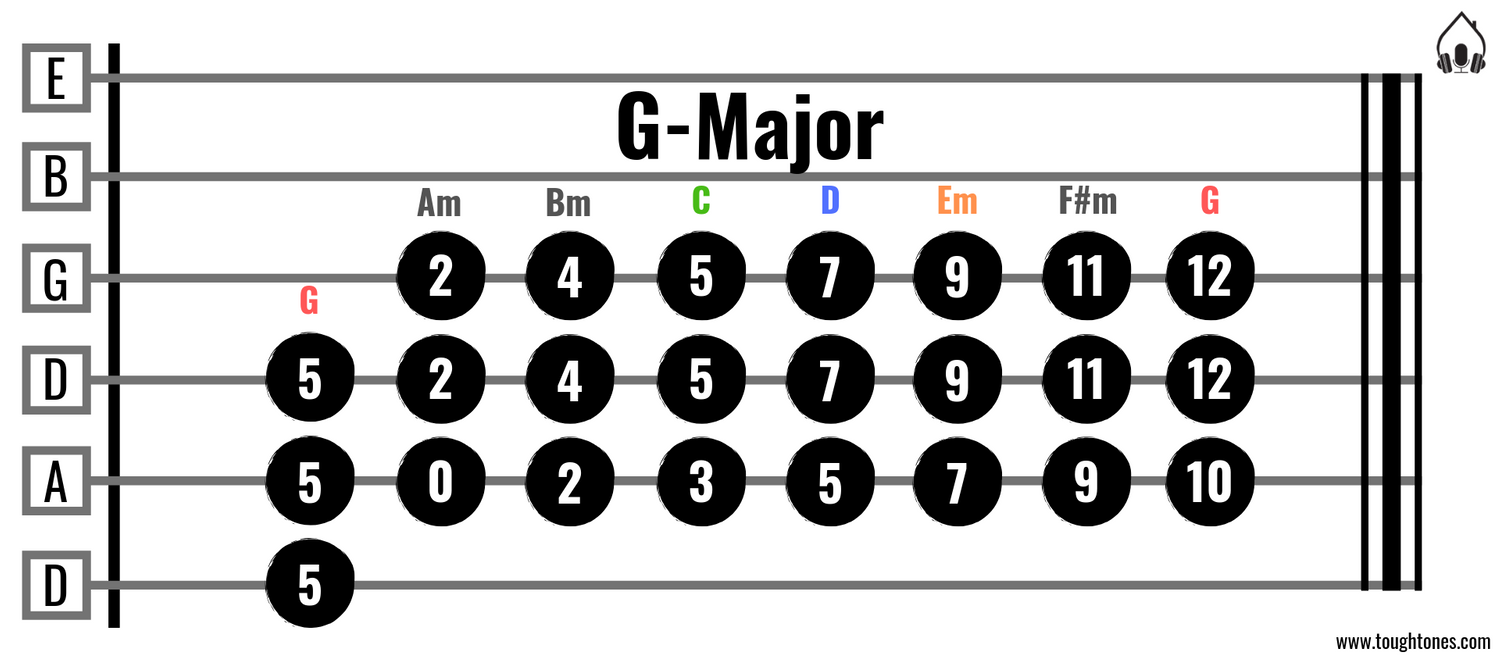

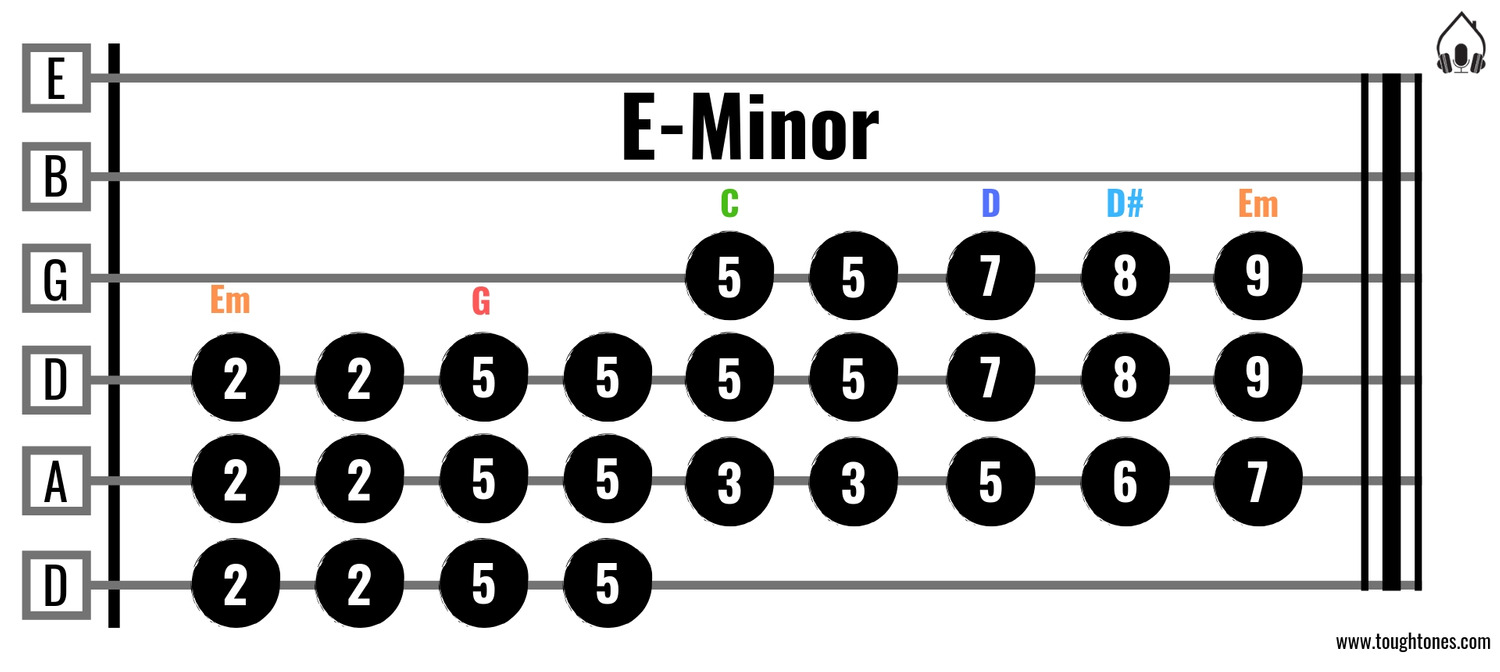

In G-major, those notes would be g, a, b, c, d, e, f#. As you can see they’re the same notes in a different order. You just start counting from a different note. The same notes fit, because they’re relatives, as we already established. These notes are used for forming chords and melodies within a given key. Here are pictures of Em and G to clarify:

In E-minor the most used chords are Em, C and D, which are the first sixth and seventh note in Em-scale. In G-major they’re G, C and D: the first the fourth and the fifth. They’re the most common chords, but by all means not the only ones. Here are all the chords within E-minor and G-major:

Let’s say you’re writing a song from E-minor. What you can do is to just start putting chord progressions together now that you know what chords to use. It makes your job a hell of a lot easier to know which chords are in your disposal. That’s why you want to know the key you’re playing and writing in.

How to Figure Out Other Keys?

Now you know Em and G, but what about all the other keys? There’s a pattern going on within the notes of a scale. Just follow the same pattern and you’ll be able to play in any key.

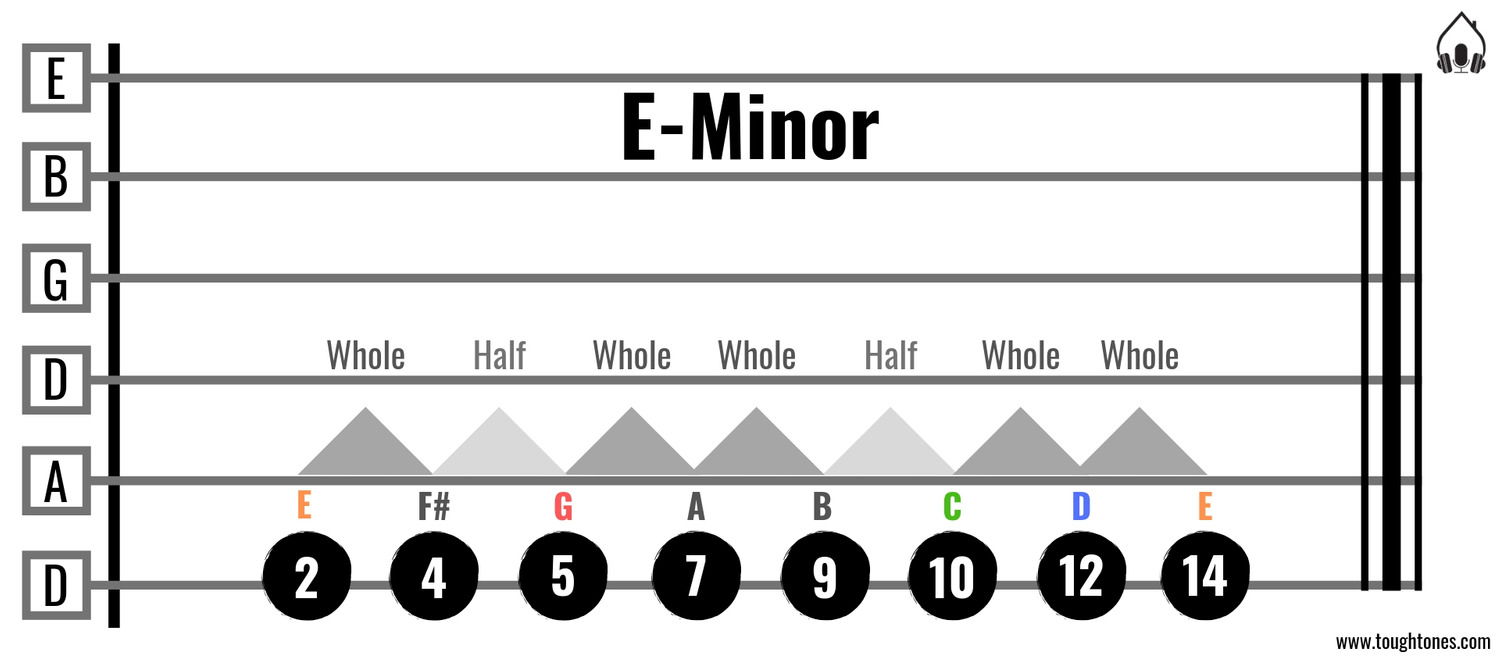

In E-minor the notes are e, f#, g, a, b, c, and d. As you take a closer look, the distances between the notes are not the same every time. From e to f# you move up two frets (from second to fourth). Whereas from f# to g you move up only one fret (from fourth to fifth). These movements are called steps: Either a half-step (one fret) or a whole-step (two frets). With these terms, from e to f# you take a whole-step and from f# to g you take a half-step. Logical, right?

After that you have a whole step again from g to a, and from a to b. Then there’s a half-step again, from b to c, followed by a whole-step from c to d and again from d back to e. This is the whole pattern: whole, half, whole, whole, half, whole, whole.

By following this pattern, you can figure out the notes and chords of other keys. You may have to count and think it through at first, but you’ll memorize the keys pretty fast once you start using them (the main three or four anyway, that you’re going to be using the most). In addition to E-minor, here are the keys that I find myself using the most:

D-Minor (F-Major)

A-Minor (C-Major)

B-Minor (D-Major)

F#-Minor (A-Major)

Scales

So that things wouldn’t get too simple, there’s different scales within the keys. The one that you’re already familiar with – the one with notes e, f#, g, a, b, c, d in E-minor – that is called a natural minor scale. The name doesn’t really matter – what matters are the notes. There are many other scales that are used to create different kinds of moods and atmospheres, especially across different cultures and genres.

Why do you want to learn other scales? Because you can compose more diverse and interesting melodies, riffs and chord progressions. I know it feels complicated, but stay with me. I’ll share you my approach to scales, that prevents you from getting overwhelmed and confused. You’ll be able to reap the benefits of various scales, without getting baffled. Sounds good enough? Let’s continue.

I use the natural minor scale as a basis for keys. I choose the chords from that scale. So in E-minor I choose chords from Em, F#m, G, Am, Bm, C and D. At the same time I know there’s other scales out there that I can exploit. For example, if I’m working on a riff or chord progression, I know I can use some other notes or chords too, in addition to the ones in natural E-minor scale.

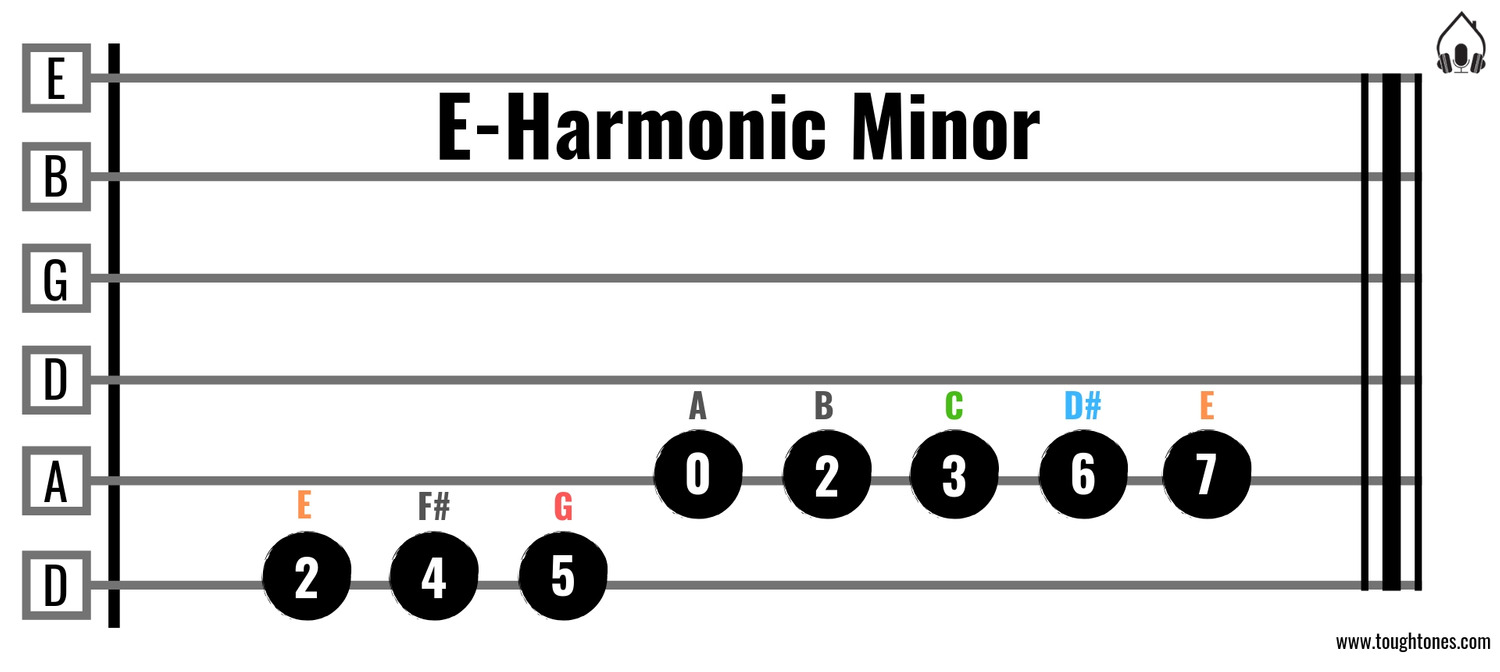

Harmonic Minor

For example here’s the harmonic E-minor scale. It’s the same as natural, but with one difference: d is replaced with d#. It’s one half step higher.

You don’t have to remember the name of the scale, all that matters are the extra notes that the scale offers. In this case the extra note is d#. Let’s say you have a chord progression of “Em, G, C, D”. You play it through the first time around like the way it is, but on the second time, you can go from D to Em through D#, like shown below. It creates a nice transition.

You can also create a new chord by using note d#. That’s a chord you can use in place of B-minor. B-major is not so sad, and has a huge pulling effect back to the first chord, whereas B-minor is really sad sounding and doesn’t pull back that much. In case you’re writing with power chords, this doesn’t really change the way you play your chord, but you could take this in concern when writing melodies.

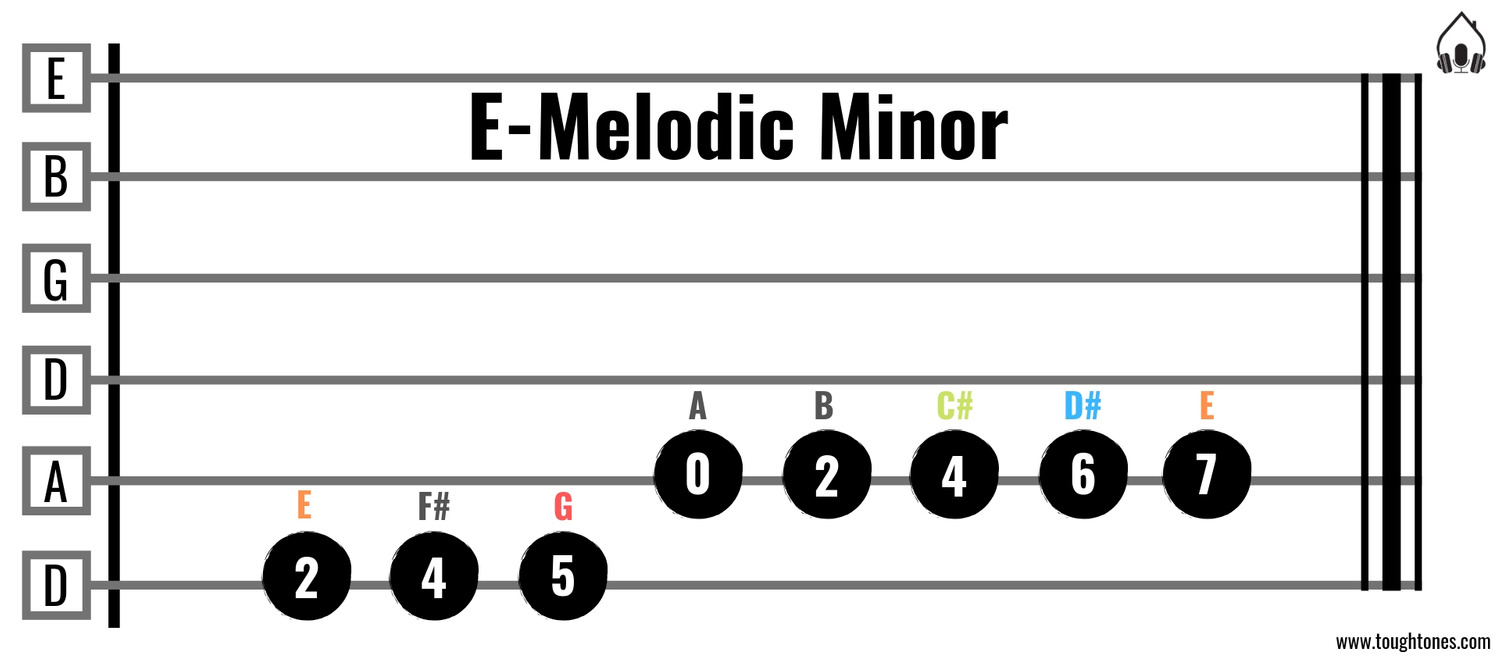

Melodic Minor

A melodic E-minor scale is a little bit similar. It has two changes compared to the natural minor scale: d → d# and c → c#. Again, just know that you can also use c# in your songs, when writing in E-minor. Let’s go with the same chord progression example that we used with harmonic minor scale. You could make the “nice transition” a little bit longer by going from C to C# to D to D# to all the way to Em.

In case you were wondering why there’s F#m chord in E-minor key, even though there’s no c# note in E-natural minor scale (as F#m chord has the note c# in it) – this is why. I didn’t want to confuse you earlier, but now you can handle this. If you were to use the basic E-natural minor scale, you would have the note c instead of c#. That would make F#m a diminished chord (also known as dim chord), because the fifth note of it would be half step lower. However, since you can take advantage of E-melodic minor scale, you can use F#m chord as it is. Of course, you can use the diminished version also, just replace the note c# with c.

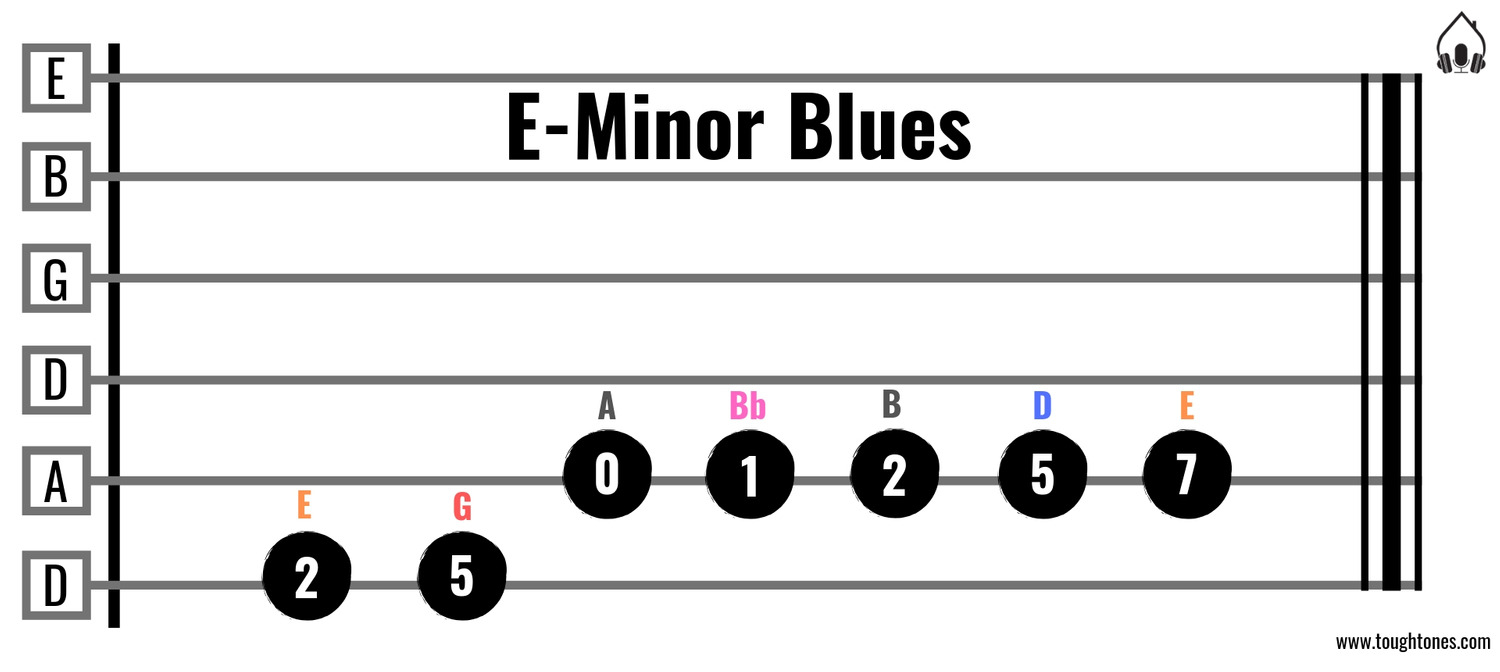

Minor Blues

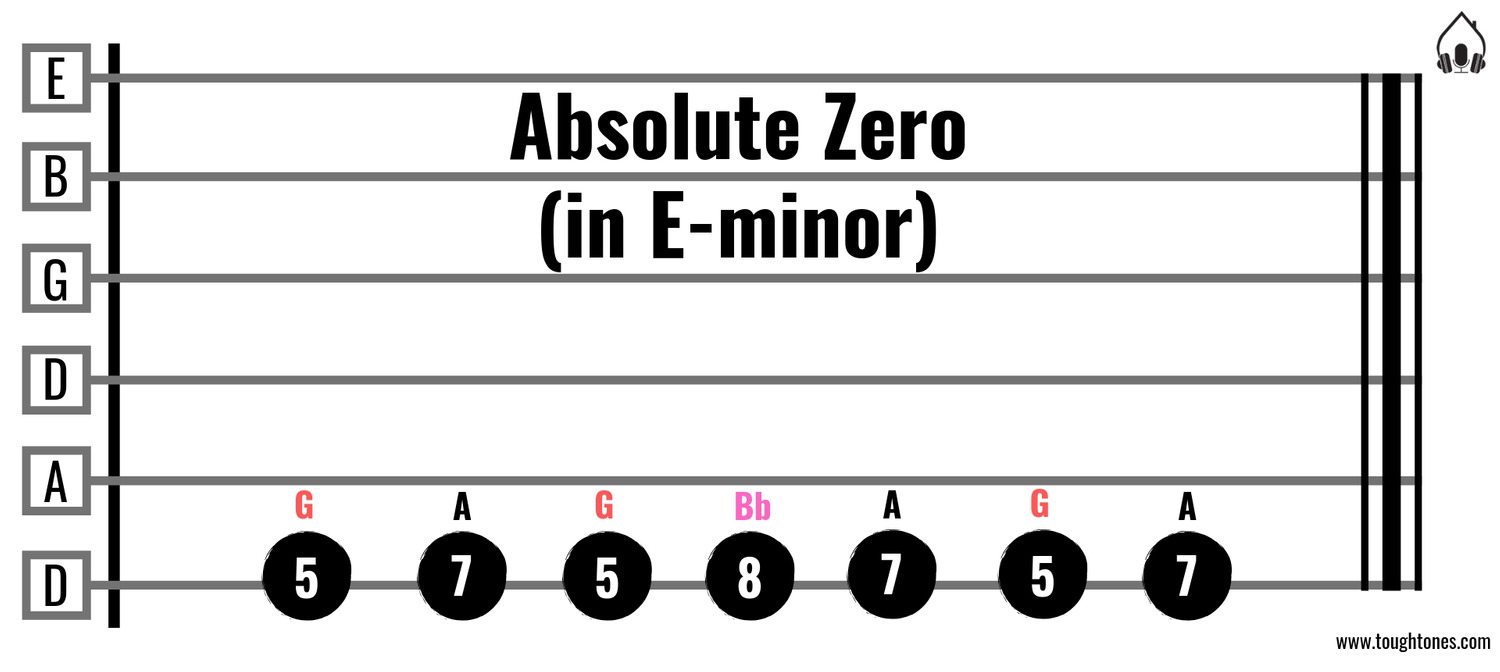

Okay, one more scale and then we’re done: E-minor blues scale. In E-minor this scale adds a note “bb” to the mix – “the blues note”. The Blues note is used a lot in riffs, for example Stone Sour – Absolute Zero. The song starts with the part of a riff that contains the blues note.

For the sake of this article and keeping things simple, I made a picture of Absolute Zero in E-minor. The original is played in D-minor, plus the tuning is half-step lower, so the actual key of it is C#-minor.

As you can see, you don’t really need to know the scales, it’s enough to know what notes they can add to your arsenal. Yes, I could’ve just told you the notes you can add, but now you know where the notes come from. They’re not just there without a foundation or a reason, there’s some logic behind it all. Of course, you can use these additional notes in any key.

How Do You Tell What Key a Song Is In?

What do you do if you want to play along with a song that you like, but there’s no chords available online? You probably swear a little and let it be or try to find the chords by ear. In that case, you should figure out the key first. Why?

Because playing along by ear becomes so much faster, as you have a certain selection of chords to play with. You don’t have to test every single chord that exists – instead you just choose from the chords that fit in that particular key. For example, if you find out that the key is Em, you already know that you have Em, G, C, D (and F#m, Am, Bm) to experiment with.

How do you figure out the key then? There are four indicators to help you determine the key:

One – The First and Last Chord

The first indicator is the first and / or last chord of a song. A song usually starts and ends with the first chord of the key (for example Em). There are exceptions, but nonetheless it’s a pretty strong sign of the key.

Two – Happy or Sad

The second indicator is listening to the song and find out if it sounds happy (major) or sad (minor). This is how you know if you should start trying chords from E-minor instead of E-major.

Three – The First Note Will Fit

The third way of knowing, is that the first note of a key will fit almost anywhere in the song. Go ahead and play the note “e” along with The Trooper by Iron Maiden or Enter Sandman by Metallica and you’ll see what I’m talking about.

Four – The Riffs

The fourth and final sign is evident especially in hard hitting metal and rock music, where there’s lots of riffs. The riffs are a strong indicator of the key you’re looking for, since they usually contain a lot of the first chord of the key. For example C-minor in the Eye of the Tiger by Survivor – and yes – Absolute Zero by Stone Sour too.

Good to Know

Here are some good to know facts, tips and tricks considering chords and keys:

These notes are actually the same:

Bb = A#

Db = C#

Eb = D#

Gb = F#

Ab = G#

It depends on the key, which way the notes are written. Don’t get confused by this.

The tuning of your guitar has an effect on the key you’re in

For example: If you’re playing in E-minor, but your tuning is a whole step down (C, G, C, F, A, D), you’re actually playing in D-minor. The same way D-minor would be a whole step lower: C-minor, etc.

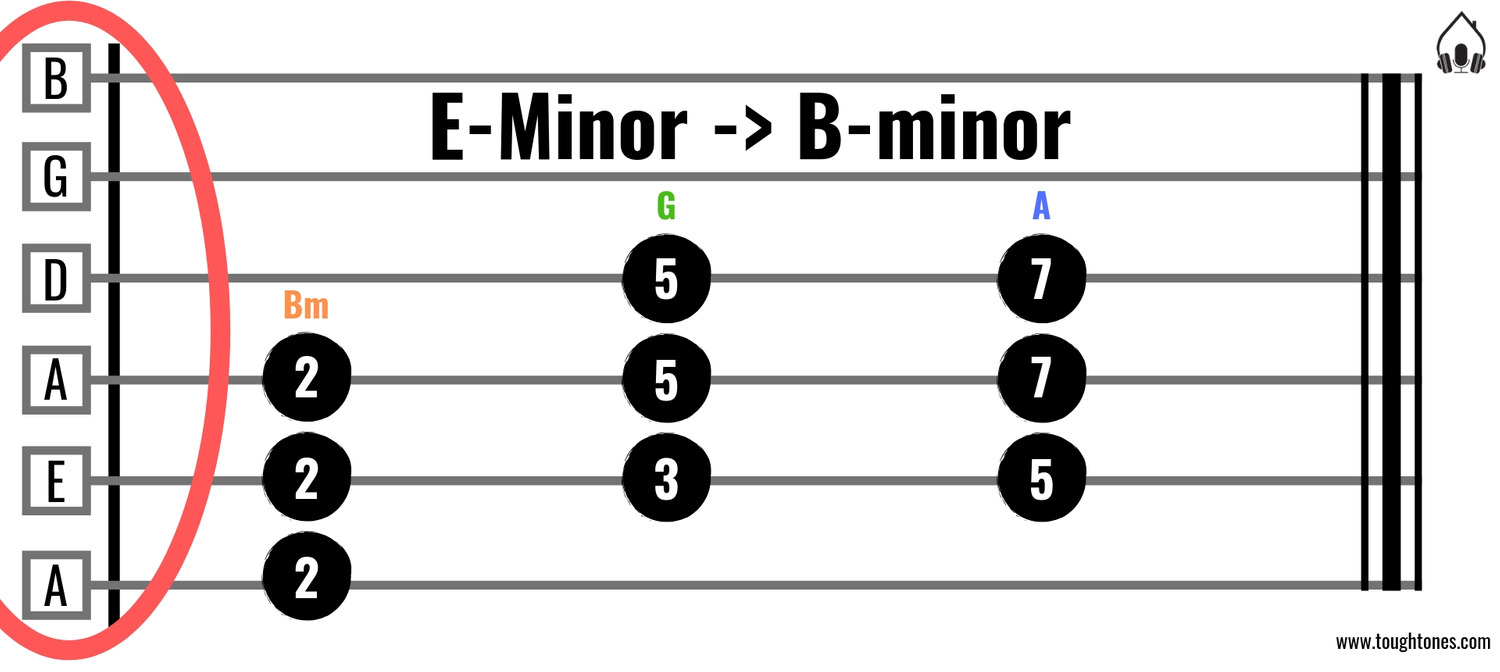

In case you are playing with a 7-string guitar and use a drop tuning (A, E, A, D, G, B, E), you can use the same chord patterns for a whole different key. For example, if you’re playing with E-minor chords “Em, C, D” you’re actually playing “Bm, G, A”. A 7-string guitar has one string below the low E-string. It’s B, unless it’s dropped down to A. Look at the picture below.

Why is this useful? You can play the same way you would in E-minor, but you can transform the song to another key, in this case B-minor. Maybe you composed the song in E-minor, but later on noticed that you can’t get the melodies high enough. That’s one reason why you’d have to change the key. Other reasons might be to get the song sounding more lower and heavier or that you want to play a riff in a certain way. With a 7-string guitar the other keys would change accordingly:

- D-minor to A-minor

- F#-minor to C#-minor

- B-minor to F#-minor

- A-minor to E-minor

Summary

You made it to the end, congratulations! Thanks for reading, I know it was a lot to take in. Keys and chords can be really frustrating, but try to keep it simple for your own sake. There’s no need to make things too complicated.

With the basic understanding of keys and chords you’ll get far with songwriting. Now you know what notes and chords to use in different keys. At least to me it was a huge breakthrough and my songwriting rose to whole another level.

Hopefully you learned a ton. Please don’t hesitate to ask if you didn’t understand something or would like to know more. Leave a comment below or shoot an email to me. Let’s sum up really briefly what we learned:

- A simple chord contains three notes: the first, the third and the fifth. The first note names the chord and the third note determines if the chord is minor or major.

-

- Minor and major chords both have one relative, for example Em and G are relatives.

-

- A key in music, is a group of notes that fit together in the same song. Once you learn one key, you can take that pattern and implement it in another key.

-

- Different scales give you extra notes for you to experiment with.

-

- The tuning of your guitar changes the key you’re playing in.

- You can figure out a key of a song by: 1. its first and last chord, 2. determining if it’s happy or sad, 3. trying to play the first note of the key along with the song, 4. focusing on riffs

Check also these useful guides to help you further with songwriting:

5 Steps to Create Music Faster (..and avoid the writer’s block!)

3 thoughts on “How to Understand Chords and Keys the Easy Way?”